United States v. Cavazos is a case out of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals (Federal). It involves an interlocutory appeal by the government after the trial court (U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas) suppressed incriminating statements made by the accused prior to receiving his Miranda warnings.

United States v. Cavazos is a case out of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals (Federal). It involves an interlocutory appeal by the government after the trial court (U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas) suppressed incriminating statements made by the accused prior to receiving his Miranda warnings.

Here’s what happened: Federal agents executed a warrant on the defendant’s home between 5:30 a.m. and 6:00 a.m. searching for evidence that he had sent sexually explicit material to a minor female. Approximately fourteen agents and officers (that’s right, 14 agents and officers!) entered the residence and handcuffed the defendant as he was getting out of bed. After the home was secured, agents removed the handcuffs and took the defendant to a bedroom for an interview. Agents told the defendant that it was a “non-custodial” interview, that he was free to get something to eat and drink during it, and that he was free to use the bathroom (they curiously left out the part about him being free to leave and free to not answer their questions and free to seek the advice of counsel, hmmm…). The agents then began questioning the defendant without reading him his Miranda rights. The defendant admitted that he had been “sexting” the victim and he described communications he had been having with other minor females.

At trial, the judge granted the defense motion to suppress the defendant’s statements made to the officers during this interrogation. The trial judge ruled that even though the officers told the defendant that the interrogation was “non-custodial,” the facts of the case proved otherwise.

On appeal, the 5th Circuit affirmed the trial court and held that the defendant was subjected to a custodial interrogation when the agents questioned him in his home. As a result, the incriminating statements made by the defendant were properly suppressed.

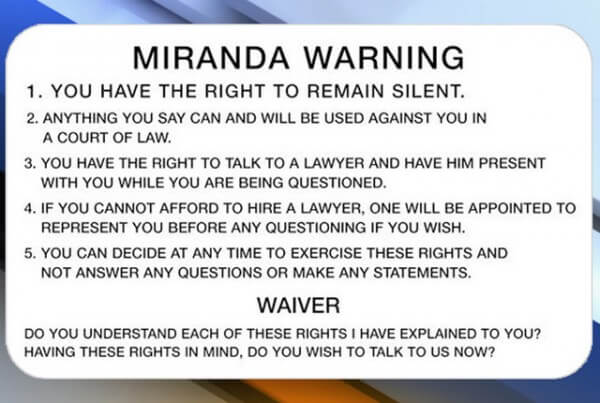

A suspect is in custody for Miranda purposes when placed under formal arrest or when a there is a restraint on his movement to the degree associated with a formal arrest, even when there is no arrest. The key question is under the circumstances, would a reasonable person have felt he was at liberty to terminate the interrogation and leave. Here, the court said no. First, fourteen agents entered the defendant’s home, in the early morning, without his consent. Second, although the defendant was free to use the bathroom or get a snack, when he did, he was followed by the agents and closely monitored. Third, although the defendant was allowed to use a telephone to call his brother, the agents had him position the phone so they could listen to the conversation. This indicated the agents’ control over the defendant while implying that he had no privacy. While the agents told the defendant the interview was “non-custodial,” such a statement made to a reasonable lay-person is not the same as telling him that he can terminate the interrogation and leave. Also, such a statement, made in a person’s home does not have the same effect as if the agents had offered to leave at any time upon request.

Overzealous agents and officers always make for good caselaw.