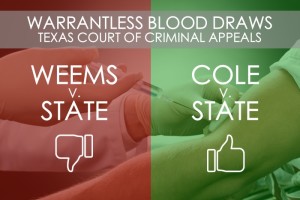

CCA Reaches Different Conclusions in Two Separate Warrantless Blood Draw DWI Cases

Just when we thought the warrantless blood draw issue was starting to reach firm footing in our appellate case law, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) throws a wrench into it. This week the CCA handed down a confounding set of opinions relating to warrantless blood draws in two separate DWI cases—Weems v. State and Cole v. State. Both cases dealt with drivers who were alleged to be intoxicated, both cases involved serious car accidents, both drivers suffered injuries, and, both cases presented law enforcement with the difficult decision to obtain blood samples without a warrant, as the body’s natural metabolic process threatened to destroy evidence over time that could have been used to charge and to prosecute the suspected intoxicated drivers. Procedurally, both Weems and Cole argue that the Texas Transportation Code § 724.012 is at odds with the Fourth Amendment and McNeely. Let’s take a look at the facts of each case and briefly review Texas law to reveal the reasoning behind the surprising conclusions reached by the CCA.

Just when we thought the warrantless blood draw issue was starting to reach firm footing in our appellate case law, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) throws a wrench into it. This week the CCA handed down a confounding set of opinions relating to warrantless blood draws in two separate DWI cases—Weems v. State and Cole v. State. Both cases dealt with drivers who were alleged to be intoxicated, both cases involved serious car accidents, both drivers suffered injuries, and, both cases presented law enforcement with the difficult decision to obtain blood samples without a warrant, as the body’s natural metabolic process threatened to destroy evidence over time that could have been used to charge and to prosecute the suspected intoxicated drivers. Procedurally, both Weems and Cole argue that the Texas Transportation Code § 724.012 is at odds with the Fourth Amendment and McNeely. Let’s take a look at the facts of each case and briefly review Texas law to reveal the reasoning behind the surprising conclusions reached by the CCA.

Two Texas CCA Opinions on Warrantless Blood Draws in DWI CasesWeems v. State

A Night of Drinking Leads to a Car Accident

FACTS: Daniel Weems drank heavily at a bar for several hours one summer evening in June of 2011. Weems decided to drive home around 11:00pm, and on the way, his car veered off the road and flipped over, striking a utility pole. A passerby stopped to help, but saw Weems exit the car through his window. When asked if he was alright, Weems stumbled around saying that he was drunk. Noticing the smell of alcohol, the passerby called 911 and watched Weems run from the scene. When the first police officer arrived at midnight, Weems was found hiding under a parked car.

Law enforcement noted his bloodshot eyes, slurred speech, and inability to stand without assistance in the police report. Moments later, a second police officer came to the scene and arrested Weems on suspicion of driving while intoxicated (“DWI”). Law enforcement decided against conducting field sobriety tests because Weems suffered injuries and had “lost the normal use of his mental and physical faculties due to alcohol.” TEX. PENAL CODE § 49.01 (2)(A). Weems, however, refused a breathalyzer and a blood test, even after law enforcement informed him of the potential consequences (suspended license, etc.) for refusal. Emergency responders transported Weems to a nearby hospital because Weems complained of neck and back pain.

Arrest Leads to Warrantless Blood Draw

Weems was seen in the hospital’s trauma unit and the second police officer completed the form, requesting a blood draw, while the first police officer remained on duty, but on standby. Weems blood was taken at 2:30 am, over two hours post-arrest, with a result of .18—well above the .08 legal limit. Relying on the Supreme Court case Missouri v. McNeely, where the highest court held that the body’s natural metabolic processing of alcohol in the bloodstream does not create an exigency (emergency) such that an exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement is created, Weems sought to have the results of the blood draw suppressed at trial. The trial court did not grant the suppression and jury found Weems guilty of felony DWI, sentencing him to eighty years’ imprisonment. On appeal, Weems argued that his Fourth Amendment rights were violated. Surprisingly, the Fourth Court of Appeals agreed with Weems, holding that in light of McNeely, Texas’s implied consent and mandatory blood draw schemes do not give way to warrant-requirement exceptions, and, that the record established at Weems’s trial did not support admitting the warrantless blood draw results under an exigency exception. The State appealed to the CCA.

Fatal Car Crash Leads to Arrest

FACTS: On a December evening in 2011, Steven Cole drove his vehicle 110 miles per hour down a busy street, running a red light, and crashing into a pickup truck. The crash caused a large explosion and fire, killing the driver of the pickup truck instantly. When the first police officer arrived at the scene around 10:30pm, he saw Cole shouting for help because he was trapped in his truck in the fire’s path. Shortly thereafter, several police officers arrived and began putting out the multiple fires to secure the area for pedestrians and motorists.

Law enforcement would later testify that “from a law enforcement and safety perspective, they needed as many officers on the scene as they could possibly get” because the raging fires and continued explosions put the public in danger. When the crash occurred, the police were in the middle of a shift change which further complicated securing the scene, conducting the investigation and maintaining public safety. Cole was eventually rescued from his truck and was examined by EMTs, to whom Cole admitted that he had taken some meth. Because of the large debris field that spanned an entire block, fourteen police officers remained at the scene to collect evidence and secure the area, which pushed the limits of the small precinct’s manpower. The debris field was not fully cleared until 6:00am—almost eight hours after the crash. Because of the size of the debris field and dangerousness of the scene requiring multiple officers to secure, only one police officer accompanied Cole to the hospital.

Suspected Intoxication Leads to Warrantless Blood Draw

At the hospital, Cole was observed complaining of pain, but also, “tweaking” and shaking—potential symptoms of suspected methamphetamine intoxication. Under a directive from the superior officer on duty, the police officer arrested Cole at 11:38pm and asked Cole for consent to collect blood and breath samples. When Cole refused, the officer read the statutory consequences for failure to consent. Cole interrupted the officer several times to comment that he had not been drinking, rather, he had taken meth. The officer made a request to the hospital for a blood draw, which was done at 12:20am. The results confirmed that Cole’s blood contained amphetamine and methamphetamine.

Cole moved to suppress the evidence at trial, but the trial court overruled the motion. The jury convicted Cole of intoxication manslaughter, sentencing Cole to a life imprisonment. On appeal, the court of appeals held that the lower court erred in not suppressing Cole’s blood draw results because State v.Villarreal “foreclosed on the State’s reliance on the mandatory blood-draw provision found in the Texas Transportation Code, and that, the trial court record did not establish that an emergency (exigency) existed to justify the warrantless blood draw. Cole v. State, 454 S.W.3d 89, 103 (Tex. App—Texarkana 2014). The State appealed to the CCA.

Law Applicable to Warrantless Blood Draws

The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides, “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause.” U.S. CONT. amend. IV. McNeely informs that blood tests are Fourth Amendment searches that implicate a “most personal and deep-rooted expectation of privacy.” McNeely, 133 S. Ct. at 1558-59 (quoting Winston v. Lee, 470 U.S. 753, 760 (1985)). Case law has determined that “a warrantless search is reasonable only if it falls within a recognized exception.” State v. Villarreal, 475 S.W.3d 784, 796 (Tex. Crim. App. 2015), reh’g denied, 475 S.W.3d 817, (Tex. Crim. App. 2015) (per curiam).

One exception to the Fourth Amendment warrant requirement is a warrantless search performed to prevent imminent evidence destruction when there is no time to secure a warrant. Cupp v. Murphy, 412 U.S. 291, 296 (1973); McNeely, 133 S. Ct. at 1559. Whether law enforcement faces an emergency that justifies acting without a warrant calls for a case-by-case determination based upon the totality of the circumstances. Id. In order for courts to determine whether an emergency existed, courts must analyze the totality of the circumstances based on an objective evaluation of the facts reasonably available to law enforcement at the time of a search, and not based on 20/20 hindsight of the facts as they are known after the fact. Brigham City, Utah v. Stuart, 547 U.S. 398, 404 (2006); Ryburn v. Huff, 132 S. Ct. 987, 992 (2012)(per curiam).

Texas Transportation Code § 724.012

Texas Transportation Code § 724.012(a) states, “specimens of a person’s breath or blood may be taken if the person is arrested and at the request of [law enforcement] having reasonable grounds to believe the person was intoxicated while operating a motor vehicle.” § 724.012(b) states, “[Law enforcement] shall require the taking of a specimen of the person’s breath or blood…if the officer arrests the person [for DUI/DWI] and the person refuses the officer’s request to submit to the taking of the specimen voluntarily…[where] any individual has died…an individual other than the person has suffered serious bodily injury.”

The CCA Weighs In—What did the CCA Decide and How Did the Judges Reach The Decisions?

In both Weems and Cole, the Court of Criminal Appeals had to determine whether the warrantless blood draws were justified by exigent (emergency) circumstances under a totality of the circumstances review of the facts. It may be surprising that in one case the CCA upheld the legality of the blood draw and in the other case the CCA held that the blood draw was unlawful. The charts below shed some light on the relevant facts of each case that the CCA reviewed to determine the holdings in each case. As you can see, the cases are quite similar, yet have some striking differences—differences that distinguished each case just enough for the CCA to arrive at opposite conclusions.

Totality of the Circumstances Analysis

Similarities Between Weems and Cole

| WEEMS | COLE |

| Refused consent to breath and blood tests. | Refused consent to breath and blood tests. |

| Driver caused car crash. | Driver caused car crash. |

| Driver injured in crash. | Driver injured in crash. |

| Admitted to drinking during initial questioning. | Admitted to using meth during initial questioning. |

| Moved to suppress evidence at trial. | Moved to suppress evidence at trial. |

| Warrantless blood draw. | Warrantless blood draw. |

| Law enforcement claimed “exigency/emergency” as reason for warrantless blood draw. | Law enforcement claimed “exigency/emergency” as reason for warrantless blood draw. |

| Law enforcement concerned BAC would fall over time, destroying potential evidence. | Law enforcement was concerned intoxication levels would fall over time, destroying potential evidence. |

Totality of the Circumstances Analysis

Differences Between Weems and Cole

| WEEMS | COLE |

| Single-vehicle crash. | Two-vehicle crash. |

| Small, rural road. | Large, high-traffic intersection. |

| Two police officers, one who remained on “stand-by”. | Entire police department tasked with maintaining and securing the exceedingly dangerous scene. |

| No deaths as a result of crash. | One fatality as a result of crash. |

| Small debris field. | Large “one block long” debris field. |

| Alcohol was the substance at issue. | Meth was the substance at issue. |

| Alcohol has a ‘known’ dissipation time. | Meth has a ‘lesser known’ dissipation time. |

| Police department’s manpower was not overwhelmed by the crash. | Police department’s manpower pushed to the limits by the crash. |

| Nothing on the record to indicate Weems was going to receive pain medication that would impact the results of a blood test. | Hospital was set to give narcotics to Cole because of pain, narcotics that could potentially impact the results of a blood test. |

The CCA’s Holding in Weems – Warrantless Blood Draw Improper

In Weems v. State, the CCA concluded that the warrantless blood draw was NOT justified by exigent (emergency) circumstances. The CCA affirmed the holding of the court of appeals that said that § 724.012 of the Texas Transportation Code does not create an exigency exception to the Fourth Amendment and that the trial court did not establish on the record any facts to support a finding of an exigent circumstance. The CCA stated that law enforcement might have had a “temporal disadvantage,” however, the time frame from the crash to the time Weems was transported to the hospital was short and that the police officer who was on standby could have called a magistrate to obtain a warrant, “the hypothetically available officer could have secured a warrant in the arresting officer’s stead.”

Further, even though the hospital took two hours to obtain the sample, such a timeframe would not have been known beforehand by law enforcement, and thus is considered “hindsight.” Hindsight is not factored into the totality of circumstances analyses. Additionally, the police department’s manpower was not completely tied up with the details of Weems’s crash. Lastly, the CCA commented that law enforcement should have protocols in place to process and deal with blood draw warrants in cases where the suspected intoxicated driver is transported to the hospital with injuries, “the record does not reflect what procedures, if any, existed for obtaining a warrant when an arrestee is taken to the hospital.”

The CCA’s Holding in Cole – Warrantless Blood Draw Authorized

In Cole v. State, the CCA held that the trial record established circumstances rendering obtaining a warrant impractical and that the warrantless search was justified under the exigency exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement. The case was reversed and remanded to the court of appeals.

The CCA said that the size and severity of the accident scene requiring several police officers to remain on the scene for public safety concerns, the large debris field that required accident investigators extended time to complete the investigation, the fact that someone died in the crash, and the fact that the dissipation rate for methamphetamine is not widely known among law enforcement the way alcohol dissipation in known, are reasons that come together to create a constellation of exigency under a totality of the circumstances analysis.

“Law enforcement was confronted with not only the natural destruction of evidence though natural dissipation of intoxicating substances, but also with the logistical and practical constraints posed by a severe accident involving a death and the attendant duties this accident demanded.” Further, because Cole complained of pain, law enforcement had a legitimate concern that any narcotic drugs administered would impact the outcome of a blood test, rendering the test ineffective for evidence in trial later on.

Justice Johnson did file a dissent in Cole, “I would hold that the circumstances and testimony at trial indicate that a warrant was required.” Justice Johnson says that someone on the police force could have obtained a warrant and had enough time to do so, “this was not a now or never situation that would relieve the state of its burden.”

Where do we go from here?

What happens when someone who illegally enters the country commits a crime? Further, does it matter is that person was previously deported from the United States? Does federal law provide for sentencing enhancements to extend the prison terms for wrongdoers in this position? The answer is yes—and no. Read on to see how the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals analyzes federal statutes and sentencing guidelines that could support such an enhancement for the defendant, but decides against doing so.

What happens when someone who illegally enters the country commits a crime? Further, does it matter is that person was previously deported from the United States? Does federal law provide for sentencing enhancements to extend the prison terms for wrongdoers in this position? The answer is yes—and no. Read on to see how the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals analyzes federal statutes and sentencing guidelines that could support such an enhancement for the defendant, but decides against doing so.

Bonsignore v State

Bonsignore v State

Just when we thought the warrantless blood draw issue was starting to reach firm footing in our appellate case law, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) throws a wrench into it. This week the CCA handed down a confounding set of opinions relating to warrantless blood draws in two separate DWI cases—Weems v. State and Cole v. State. Both cases dealt with drivers who were alleged to be intoxicated, both cases involved serious car accidents, both drivers suffered injuries, and, both cases presented law enforcement with the difficult decision to obtain blood samples without a warrant, as the body’s natural metabolic process threatened to destroy evidence over time that could have been used to charge and to prosecute the suspected intoxicated drivers. Procedurally, both Weems and Cole argue that the Texas Transportation Code § 724.012 is at odds with the Fourth Amendment and

Just when we thought the warrantless blood draw issue was starting to reach firm footing in our appellate case law, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) throws a wrench into it. This week the CCA handed down a confounding set of opinions relating to warrantless blood draws in two separate DWI cases—Weems v. State and Cole v. State. Both cases dealt with drivers who were alleged to be intoxicated, both cases involved serious car accidents, both drivers suffered injuries, and, both cases presented law enforcement with the difficult decision to obtain blood samples without a warrant, as the body’s natural metabolic process threatened to destroy evidence over time that could have been used to charge and to prosecute the suspected intoxicated drivers. Procedurally, both Weems and Cole argue that the Texas Transportation Code § 724.012 is at odds with the Fourth Amendment and

On April 20, 2016, the Supreme Court of the United States (“SCOTUS”) heard

On April 20, 2016, the Supreme Court of the United States (“SCOTUS”) heard

James Leming was convicted of DWI after erratic driving alarmed fellow motorists to call police. On January 20, 2012, a citizen filed a report of a “swerving Jeep” and Officer Manfred Gilow responded. As the dashboard camera confirmed, the Jeep traveled thirteen miles under the speed limit; Gilow followed the Jeep for several miles. Officer Gilow observed the Jeep, “drifting [within the] lane to the left [with] tires on the stripes… back to the right, almost hit[ting] the curb twice.”

James Leming was convicted of DWI after erratic driving alarmed fellow motorists to call police. On January 20, 2012, a citizen filed a report of a “swerving Jeep” and Officer Manfred Gilow responded. As the dashboard camera confirmed, the Jeep traveled thirteen miles under the speed limit; Gilow followed the Jeep for several miles. Officer Gilow observed the Jeep, “drifting [within the] lane to the left [with] tires on the stripes… back to the right, almost hit[ting] the curb twice.”

We’ve all signed the “HIPAA” privacy statements at the doctor’s office before treatment. The HIPAA Privacy Rule mandates nationwide standards to protect our medical records and personal health information by establishing safeguards, such as disclosure rules, patient authorization, and uniform protocols for the electronic transmission of medical data. HIPAA also grants patients the right to their own health information, but what about others? Does HIPAA prohibit the release of health information in a criminal investigation? What if that information is obtained via a grand jury subpoena?

We’ve all signed the “HIPAA” privacy statements at the doctor’s office before treatment. The HIPAA Privacy Rule mandates nationwide standards to protect our medical records and personal health information by establishing safeguards, such as disclosure rules, patient authorization, and uniform protocols for the electronic transmission of medical data. HIPAA also grants patients the right to their own health information, but what about others? Does HIPAA prohibit the release of health information in a criminal investigation? What if that information is obtained via a grand jury subpoena?

Louis Jarvis, Jr. and his wife Jennifer Jones were charged with driving while intoxicated arising out of separate but related incidents on the same evening. Both pled no contest to the charges against them. But before they were found guilty, it was discovered that neither complaint against Jarvis or Jones alleged a year that the offense was committed. The trial court granted their motions to acquit. The State appealed.

Louis Jarvis, Jr. and his wife Jennifer Jones were charged with driving while intoxicated arising out of separate but related incidents on the same evening. Both pled no contest to the charges against them. But before they were found guilty, it was discovered that neither complaint against Jarvis or Jones alleged a year that the offense was committed. The trial court granted their motions to acquit. The State appealed.

Do you have a DWI conviction in Texas (or anywhere in the United States)? Are you traveling to Canada any time soon? If you answered “Yes” to both of these questions, you may be in for a surprise at the border. Even if you have recently been acquitted of a DWI charge, you may still be turned away and deemed “criminally inadmissible for entry.” This article will explain the law and provide some solutions if you find yourself in this dilemma.

Do you have a DWI conviction in Texas (or anywhere in the United States)? Are you traveling to Canada any time soon? If you answered “Yes” to both of these questions, you may be in for a surprise at the border. Even if you have recently been acquitted of a DWI charge, you may still be turned away and deemed “criminally inadmissible for entry.” This article will explain the law and provide some solutions if you find yourself in this dilemma.

Tarrant County has many

Tarrant County has many