Illegal Search and Seizure Defense Attorneys

What exactly is a “Consensual Encounter” between a police officer and a citizen? The trend in Texas search and seizure law over the past several years seems to indicate that any time a police officer does not have reasonable suspicion to justify a detention of an individual (or probably cause to arrest), the courts label the unreasonable detention as a “consensual encounter,” thereby justifying the illegal search and sustaining the investigative actions that follow. The courts reason that the citizen was free to leave at any time during the officer’s questioning so the 4th Amendment is not implicated.

What exactly is a “Consensual Encounter” between a police officer and a citizen? The trend in Texas search and seizure law over the past several years seems to indicate that any time a police officer does not have reasonable suspicion to justify a detention of an individual (or probably cause to arrest), the courts label the unreasonable detention as a “consensual encounter,” thereby justifying the illegal search and sustaining the investigative actions that follow. The courts reason that the citizen was free to leave at any time during the officer’s questioning so the 4th Amendment is not implicated.

My question has always been” “Exactly what do you think the officer would have done if the person tried to leave during this encounter?” In the case that follows, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals takes a huge step in the right direction against “consensual encounters.”

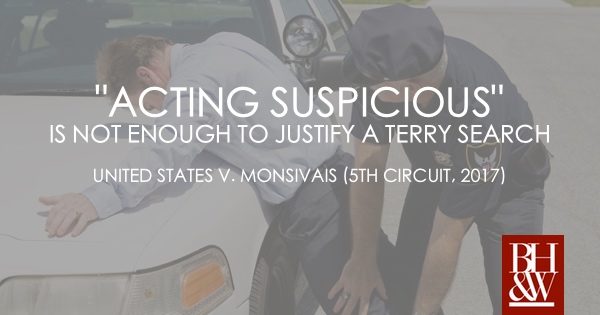

Johnson v. State – One night, a resident of an apartment complex called 911 to report a suspicious person- an unidentified black male who was sitting out front of the leasing office watching cars. In response to her call, a Houston Police officer went to the complex. Although the officer did not see anyone outside the leasing office, he noticed a vehicle that was backed into a parking space with its lights on. The officer parked his car in a manner in which the appellant would have had to maneuver around the car to leave and shined his high-beam spotlight in the car. Believing that appellant could be the suspect, the officer approached the driver side door where he smelled an odor of marijuana. Despite the fact that the appellant’s clothing did not match the description given by the resident, the officer spoke to the appellant using a ‘loud authoritative voice.’ During the officer’s interaction with the appellant, he smelled an odor of marijuana coming from inside the car. The officer did not see the marijuana until after he asked appellant to step out of the car. The officer arrested the appellant and charged him with misdemeanor possession of marijuana.

Appellant filed a motion to suppress asserting that his seizure was made without any reasonable suspicion that he was engaged in any criminal activity and that the acquisition of the evidence was not pursuant to a reasonable investigative detention or pursuant to an arrest warrant. The trial court denied the motion holding that appellant had been detained and that the officer acted reasonably under the circumstances and did have articulable facts that justified the minimal detention. The court of appeals affirmed the trial court’s judgment holding that a reasonable person in appellant’s position would have believed that he was free to ignore the officer’s request or terminate the interaction, thus making the initial interaction a consensual encounter rather than a Fourth Amendment seizure.

Police and citizens may engage in three distinct types of interactions: consensual encounters, investigative detentions, and arrests. Consensual police-citizen encounters do not implicate Fourth Amendment protections. But, when a seizure takes the form of a detention, Fourth Amendment scrutiny is necessary and it must be determined whether the detaining officer had reasonable suspicion that the citizen is, has been, or is about to be engaged in criminal activity.

On review of the denial of appellant’s motion to suppress evidence that led to his marijuana conviction, the Court of Criminal Appeals held that the court of appeals erred in holding that the officer did not detain the appellant. Under the totality of the circumstances, a reasonable person would not have felt free to leave. When the officer (1) shined his high-beam spotlight into appellant’s vehicle, (2) parked his police car in such a way as to at least partially block appellant’s vehicle, (3) used a “loud authoritative voice” in speaking with appellant, (4) asked “what’s going on,” and (5) demanded identification, a detention manifested. The Court of Criminal Appeals reversed and remanded the case to the court of appeals to consider the trial court’s determination that the officer had reasonable suspicion to detain the appellant and to decide whether that detention was valid.