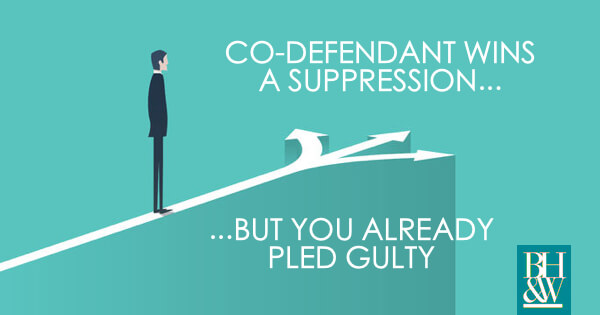

“Buyer’s Remorse”—Rolling the Dice on Plea Deals

The Court of Criminal Appeals recently handed down an opinion concerning a motion for a new trial based on evidence obtained from a co-defendant’s motion to suppress hearing. The issues facing the Court were whether the defendant, who had recently entered into a plea deal, satisfied the requirements for granting a new trial on the basis of such evidence; and, whether the defendant’s ineffective assistance of counsel claim was properly brought before the court.

The Court of Criminal Appeals recently handed down an opinion concerning a motion for a new trial based on evidence obtained from a co-defendant’s motion to suppress hearing. The issues facing the Court were whether the defendant, who had recently entered into a plea deal, satisfied the requirements for granting a new trial on the basis of such evidence; and, whether the defendant’s ineffective assistance of counsel claim was properly brought before the court.

State of Texas v. Arizmendi (Court of Criminal Appeals, 2017)

The Facts — Trial Court Granted Defendant’s Motion for New Trial in the “Interest of Justice.”

Rosa Arizmendi, Defendant, was convicted (after pleading guilty) for being in possession of more than 400 grams of methamphetamine with intent to deliver after officers stopped her co-defendant’s vehicle, of which she was a passenger. Both Defendant and Co-defendant were arrested as a result of the stop. On April 28, 2015, Defendant entered into a plea deal, receiving twenty-five years confinement and a $5,000 fine. Additionally, Defendant voluntarily waived her right to appeal.

Six days later, a hearing for a motion to suppress was held regarding Co-defendant’s case. The video of the stop was introduced into evidence, and the arresting officer testified, noting that he initially noticed the vehicle because it looked clean and subsequently stopped the vehicle for crossing over the while line delineating the roadway from the improved shoulder. However, the trial court concluded that Co-defendant’s vehicle was not in any violation of Texas law. The Court explained that the vehicle only came in close proximity of and possibly touched the inside portion of the white line, which is not a violation of Texas law. Thus, granting Co-defendant’s motion. See, State v. Cortez, 501 S.W.3d 606 (Tex. Crim. App. 2016).

Based on this information, Defendant filed a motion for new trial, “in the interest of justice,” alleging the verdict in her case was contrary to the law and evidence. Defendant’s motion referred to Co-defendant’s hearing alleging a lack of probable cause or other lawful reasons for the stop. Furthermore, Defendant asserted the officer’s testimony was new evidence not available at the time of Defendant’s guilty plea. Defendant’s counsel further asserted that because she failed to tell Defendant that a motion to suppress was an option, Defendant received ineffective assistance.

The State argued that Defendant waived her right to appeal as a result of the plea deal and had not presented any new evidence likely to result in a different ruling. Noting, all evidence could have been discovered had Defendant been diligent. The State further asserted that Defendant was merely suffering from “buyers remorse.” Moreover, the State contended Defendant’s ineffective assistance claim was not apart of the original motion for new trial and, therefore, was untimely. However, the trial court rejected these arguments and granted Defendant’s motion for new trial “in the interest of justice,” and the State appealed.

The Court of Appeals Affirmed the Trial Court’s Decision — Holding Defendant Satisfied the Requirements for Granting a New Trial Based on Newly Discovered Evidence.

On appeal the State contended that the trial court abused its discretion in granting Defendant’s motion and further reiterated its previous assertions.

The Court of Appeals, however, rejected the State’s arguments. The Court held Defendant’s motion was not barred because the trial court implicitly granted Defendant permission to appeal when it set Defendant’s motion for hearing. The Court also determined Defendant did, in fact, present new evidence. The video of the stop did not contain audio and, therefore, the testimony was new because it was not available at the time of Defendant’s plea. Accordingly, since the Court found there was new evidence they declined to rule on the ineffective assistance claim and affirmed the trial court’s ruling.

The Court of Criminal Appeals Reversed and Remanded — Holding Defendant did not Satisfy the Requirements for Relief.

The State appealed again and the Court of Criminal Appeals reversed the lower courts’ decisions. Here, Defendant pled guilty pursuant to a plea deal and after learning of her co-defendant’s favorable outcome Defendant filed a motion for new trial. The Court concluded that Defendant’s assertions were without merit because her failure to discover “new evidence” was a result of her own lack of due diligence. Furthermore, the “new evidence” Defendant asserts was either cumulative, collateral, or would not have brought about a different result.

To obtain relief the Court noted Defendant must satisfy the following four-prong test:

• The newly discovered evidence was unknown or unavailable to Defendant at the time of trial;

• Defendant’s failure to discover or obtain the new evidence was not due to the defendant’s lack of due diligence;

• The new evidence is admissible and not merely cumulative, corroborative, collateral, or impeaching; and,

• The new evidence is probably true and will probably bring about a different result in a new trial.

Defendant asserted the following as newly discovered evidence:

• The trial court’s ruling on Co-defendant’s motion to suppress;

• The testimony of the arresting officer at Co-defendant’s suppression hearing; and,

• The arresting officer’s statement about Defendant’s vehicle being a clean vehicle.

First, the Court explained that the trial court’s ruling on the motion to suppress was not evidence; it was only a legal determination. And, furthermore, even if it was considered evidence Defendant’s failure to discover was due to her own lack of due diligence. Second, the officer’s testimony was evidence, but aside from the testimony regarding the clean vehicle, it was merely cumulative and Defendant had access to the video, which conveyed the very same facts as the testimony. Furthermore, the Court determined the officer’s testimony regarding the clean vehicle was collateral, at best. The Court explained that the officer’s subjective intent was irrelevant to the ruling. Moreover, Defendant could have sought a police report or even filed her own motion to suppress to obtain such evidence—just as her co-defendant did. Finally, the Court concluded that Defendant’s ineffective assistance claim was not properly before the court because it was not made within thirty days of the judgment and, therefore, was untimely.

Thus, all evidence Defendant asserts as “new” was either cumulative, collateral, or would not have brought about a different result. As such, the Court reversed the lower courts’ decisions and remanded with instructions to reinstate Defendant’s judgment and sentence.

This case prompted two concurring opinions and a dissent. See below.

Arizmendi Hervey Concurrence

Arizmendi Newell Concurrence

Arizmendi Alcala Dissent

Takeaways

It is paramount that defense attorneys review all evidence and timely seek any additional evidence that may be relevant to a client’s case. Moreover, it is crucial for attorneys to provide clients with all possible options and outcomes before entering into a plea deal. Here, Defendant had all the same options as her co-defendant; however, Defendant was not properly counseled and, consequently, Defendant will spend twenty-five years in prison while her co-defendant remains free.

The Court of Criminal Appeals recently handed down an opinion on a petition for writ of mandamus in regard to a discovery dispute arising out of

The Court of Criminal Appeals recently handed down an opinion on a petition for writ of mandamus in regard to a discovery dispute arising out of

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently handed down an opinion concerning the reasonable suspicion standard required for law enforcement officers to conduct a Terry stop—an exception to the warrant requirement. The issue facing the Court was whether merely “acting suspicious” is enough to establish reasonable suspicion to justify a law enforcement officer to initiate a Terry stop.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently handed down an opinion concerning the reasonable suspicion standard required for law enforcement officers to conduct a Terry stop—an exception to the warrant requirement. The issue facing the Court was whether merely “acting suspicious” is enough to establish reasonable suspicion to justify a law enforcement officer to initiate a Terry stop.

In general, resisting arrest occurs when a person attempts to interfere with a peace officer’s duties.

In general, resisting arrest occurs when a person attempts to interfere with a peace officer’s duties.