From call logs, to cell tower info, to sent and received text messages, many criminal investigations involve the contents of a defendant’s cell phone. Under the Stored Communications Act, cell phone providers can provide a users cell phone data to police during an active criminal investigation with a simple court order (like a subpoena). But what about the actual content of text messages? Can the police or the prosecutor get the actual content from those text messages with the same court order?

From call logs, to cell tower info, to sent and received text messages, many criminal investigations involve the contents of a defendant’s cell phone. Under the Stored Communications Act, cell phone providers can provide a users cell phone data to police during an active criminal investigation with a simple court order (like a subpoena). But what about the actual content of text messages? Can the police or the prosecutor get the actual content from those text messages with the same court order?

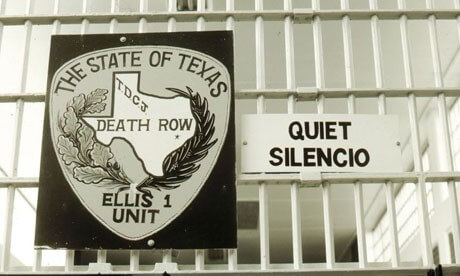

Capital Murder Conviction Gained After Judge Admits Content of Text Messages

Recently, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals considered a capital murder (death penalty) case in which the State relied on text message evidence during trial. During the trial, the state admitted (over defense objection) the contents of text messages sent and received by the defendant. The messages established the defendant’s presence at the scene of the murder and implied his direct involvement. The state leaned on this evidence during both its opening and closing statements in the case. The defendant was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death.

The Content of Text Messages are Not Covered by the Stored Communications Act

The appellant argued on appeal that while the Stored Communications Act allows the state to gain evidence of text messages sent and received, it does not allow the dissemination of the content of those messages. The appellant argued that the State should have obtained a search warrant backed by probable cause in order to get these records. The CCA agreed, drawing comparisons to the contents of letters sent in the mail and email stored on a server. Text message enjoy the same reasonable expectation of privacy and should be protected.

The Question in Love v. State is Whether Appellant had an Expectation of Privacy in his Service Provider’s Records

LOVE v. STATE (Tex. Crim. App – 2016), Majority Opinion

Judge Yeary penned the majority opinion in Love. The following excerpts are taken from the opinion:

Many courts have treated text messages as analogous to the content of an envelope conveyed through the United States mail…Admittedly, the analogy is not a perfect one…A letter remains in its sealed envelope until it arrives at its destination, and the telephone company does not routinely record private telephone conversations. But internet and cell phone service providers do routinely store the content of emails and text messages, even if they do not necessarily take the time to read them…[E]mpirical data seem to support the proposition that society recognizes the propriety of assigning Fourth Amendment protection to the content of text messages…All of this leads us to conclude that the content of appellant’s text messages could not be obtained without a probable cause–based warrant. Text messages are analogous to regular mail and email communications. Like regular mail and email, a text message has an “outside address ‘visible’ to the third-party carriers that transmit it to its intended location, and also a package of content that the sender presumes will be read only by the intended recipient…Consequently, the State was prohibited from compelling Metro PCS to turn over appellant’s content-based communications without first obtaining a warrant supported by probable cause.

Finding that “the probable impact of the improperly-admitted text messages was great,” the CCA then reversed the conviction and remanded the case back to the trial court for a new trial.

TAKEAWAY: Not all records can be gained so easily through a court order. Some require a probably cause warrant. Is there a reasonable expectation of privacy in the message? It might take a new analysis as our media is changing daily, but it can be worth the fight.

Note: Presiding Judge Keller dissented. She did not believe that the appellant preserved this issue for appeal.

Pantoja v. State

Pantoja v. State

Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Section 38.43 deals with “Biological Evidence,” and outlines the rules and responsibilities for testing such evidence. In the mandamus case summary that follows, the relator (the defendant) is requesting that ALL of the biological evidence be tested, while the trial judge has ruled that only some testing is sufficient.

Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Section 38.43 deals with “Biological Evidence,” and outlines the rules and responsibilities for testing such evidence. In the mandamus case summary that follows, the relator (the defendant) is requesting that ALL of the biological evidence be tested, while the trial judge has ruled that only some testing is sufficient.

In 2002, the United States Supreme Court determined that the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment bars the execution of mentally retarded persons. Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

In 2002, the United States Supreme Court determined that the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment bars the execution of mentally retarded persons. Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

The Court of Criminal Appeals does not like dog scent lineup evidence. While it has not come right out and declared such evidence categorically inadmissible (like polygraph evidence), it seems pretty close. With each new dog scent lineup case, we learn how unreliable this type of evidence can be.

The Court of Criminal Appeals does not like dog scent lineup evidence. While it has not come right out and declared such evidence categorically inadmissible (like polygraph evidence), it seems pretty close. With each new dog scent lineup case, we learn how unreliable this type of evidence can be.