United States Supreme Court | Search and Seizure Update

We expect that police officers know the law. After all, they are charged with upholding the law. But what happens when an officer makes a traffic stop based on an incorrect understanding of the law and then finds evidence of another crime during his improper stop? The Supreme Court recently considered this scenario in the case outlined below:

We expect that police officers know the law. After all, they are charged with upholding the law. But what happens when an officer makes a traffic stop based on an incorrect understanding of the law and then finds evidence of another crime during his improper stop? The Supreme Court recently considered this scenario in the case outlined below:

In Heien v. North Carolina, a North Carolina police officer stopped a man for driving with one broken brake light. The driver later gave consent to the officer to search his vehicle. The officer discovered cocaine charged the driver with trafficking cocaine. The driver argued that the officer made a mistake of law for stopping him on one faulty brake light and not two (which is what NC law requires) therefore evidence should be suppressed. The NC vehicle code makes clear that the officer was mistaken when making the traffic stop.

The Supreme Court granted cert to review the case and the question of whether an officer who makes a mistake of law still gives rise to reasonable suspicion. They Court ruled that the officer’s mistake of law was objectively reasonable and that ultimately, the Officer had reasonable suspicion to conduct the traffic stop. In so holding, Chief Justice Roberts wrote “The Fourth Amendment requires government officials to act reasonably, not perfectly, and gives those officials ‘fair leeway for enforcing the law.'”

While not dealing with specific state law in Texas, the ruling in this case did address reasonable suspicion as it relates to unreasonable searches prohibited by the 4th Amendment. Article 38.23 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure states:

No evidence obtained by an officer or other person in violation of any provisions of the Constitution or laws of the State of Texas, or of the Constitution or laws of the United States of America, shall be admitted in evidence against the accused on the trial of any criminal case.

While Article 38.23 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure provides an exception if an officer is acting in objective good faith reliance on a warrant, it does not give a reasonable suspicion exception to conduct a search. Clearly, the Heien opinion will be cited by the State to support searches even when the initial stop is conducted illegally. We will just have to wait and see how our Texas Courts will react in light of Heien v. North Carolina.

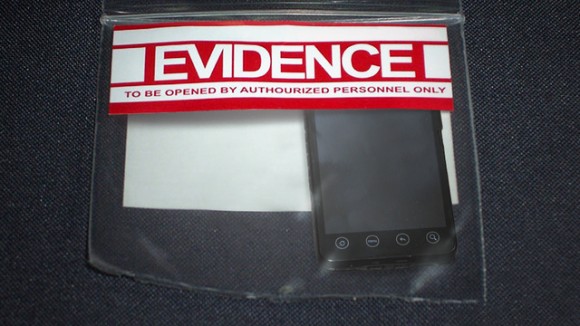

U.S. Supreme Court Holding: YES – The 4th Amendment prohibits officers from searching a suspects cell phone for information without a warrant.

U.S. Supreme Court Holding: YES – The 4th Amendment prohibits officers from searching a suspects cell phone for information without a warrant.

In any criminal case involving sexual exploitation of a child in the making, possessing, or distributing of child pornography, there is an issue of restitution to consider. More specifically, if the child suffered monetary damages, who is responsible to pay restitution to the child to make him/her whole? Is it the person that created the images, the person that distributed them on the internet, the end user that downloads and possesses the images, or everyone? The courts were split on this issue. Some held that every person along the way should pay their share of the damages. Other courts held that each person is responsible for the total damages.

In any criminal case involving sexual exploitation of a child in the making, possessing, or distributing of child pornography, there is an issue of restitution to consider. More specifically, if the child suffered monetary damages, who is responsible to pay restitution to the child to make him/her whole? Is it the person that created the images, the person that distributed them on the internet, the end user that downloads and possesses the images, or everyone? The courts were split on this issue. Some held that every person along the way should pay their share of the damages. Other courts held that each person is responsible for the total damages.

Issue presented to the Court: Whether Appellant’s state court assault conviction qualified as a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence” thereby prohibiting him from possessing a firearm under federal law (18 U.S.C. §922(g)(9)).

Issue presented to the Court: Whether Appellant’s state court assault conviction qualified as a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence” thereby prohibiting him from possessing a firearm under federal law (18 U.S.C. §922(g)(9)).

The Supreme Court said YES in

The Supreme Court said YES in

Let’s face it, nobody really likes uninvited guests on their front porch, unless, of course, it is the time of year when the Girl Scouts are selling cookies or little trick-or-treat monsters are out and about. Aside from that, I’m not too keen on having people drop by unannounced, especially if that person is trying to investigate a crime or conduct a search and seizure.

Let’s face it, nobody really likes uninvited guests on their front porch, unless, of course, it is the time of year when the Girl Scouts are selling cookies or little trick-or-treat monsters are out and about. Aside from that, I’m not too keen on having people drop by unannounced, especially if that person is trying to investigate a crime or conduct a search and seizure.

A federal agent saw Appellant walk out of a house under surveillance as part of a

A federal agent saw Appellant walk out of a house under surveillance as part of a